In Glasgow, the question “Do you think I came up the Clyde in a banana boat?” means do you think I am stupidly naive? The relevance of this title will, I trust, become clear as we proceed through this history.

The 1946 Scottish Committee on Homeless Children, under the chairmanship of James L. Clyde KC (The Clyde Committee), was given a remit

“to inquire into the existing methods of providing for children deprived of normal home life, and to consider what further measures should be taken to compensate them for lack of parental care”.

Compensate in this context denotes an artificial replacement of normal family life by the state as a benign savior.

The Clyde report concluded that:

The lesson which above all else the war years have taught us is the value of home. It is upon the family that our position as a nation is built, and it is to the family that in trouble and disaster each child naturally turns. It is the growing awareness of the importance of the family which has largely brought into prominence the problem of the homeless child. How then is the family to be re-created for the child who is rendered homeless?

The report for the Scottish Child Abuse Inquiry made by Professor Kenneth McKenzie Norrie of The University of Strathclyde Law School summarises the objectives of the Clyde Report and the legislation that came from it as follows:

State provision of substitute families, which would replace the unsatisfactory families from which children or young persons had been removed, was therefore seen as the primary solution to lack of parental care. The Report’s preference for foster parents over institutional care was underpinned by a belief, which may strike the modern reader as naïve, that “parental affection” would always be an inherent part of the care offered by those fostering children.

Norrie continues:

It is striking that there is so little in the Clyde Report about working with the child’s own family to allow its return, other than the sole, and substantially qualified, assertion that “every encouragement should be given to … a reunion of the family (if the parents are satisfactory)”. Nor is there anything about parental contact with children accommodated away from their parents: the aim is plainly to insulate the child from the harmful environment from which he or she has been removed.

In other words, the state decided that it could, and should, synthesise artificial families where it found natural ones to be unsatisfactory. Norrie summarised this as follows:

The aim of the 1932, 1937 and 1948 Acts was to ensure that the child would be provided with family life by the state: just not with their own family.

This was of course part of the huge expansion of the welfare state that was brought in by the socialist government of Clement Attlee and forms a piece with the National Insurance Act 1946, the National Health Service (Scotland) Act 1947, and the National Assistance Act 1948.

As the father of modern English family law, Professor Stephen Cretney said:

The notion that the community should charge itself with specific responsibility to provide care for all children deprived of a normal home life – and not merely to secure the subsistence of the destitute and, at the other extreme, to provide through the wardship jurisdiction for the affairs of the wealthy – was wholly novel; and in this respect the Children Act 1948 surely deserves to be remembered as one of the cornerstones of the post-war welfare State.

So what, exactly was involved in all of this? Well, there was a committee, isn’t there always: A Children’s committee. And here, our story gets very dark. The power invested in these committees (every local authority had to have one) is almost beyond belief. They could pass a “parental rights resolution” and remove a child from his or her family without further ado. Reasons for removing a child could include the committee deciding that the parents were:

…of such habits or mode of life as to be unfit to have the care of the child.

No court was involved, and no standards of evidence were laid down. It was simply the decision of the committee. As Norrie comments:

There were antecedents in English law, but none in Scots law, to institutions taking over parental rights without court process.

It was up to the parent, after the removal of their child to go to court to have the matter overturned. A complaint could be submitted to the court and, if a court order was obtained, the child would be returned to the parents. The child’s removal, however, required only a majority vote in the committee.

Oddly, this innovation in Scots law was brought in from the English Poor Laws, but was not favoured by the English equivalent to the Clyde Committee, The Curtis Committee, who stated that:

We think it objectionable… that the rights of a parent or other guardian should be extinguished by a mere resolution of a Council.

This obscene power, granted to Scottish local authorities in 1948 was re-enacted, with only minor modifications in the Social Work (Scotland) Act 1968. It was only abolished by the Children (Scotland) Act in 1995. Thus for nearly fifty years, Scottish Local Authorities could vote to remove any child from its parents and there was nothing the parents could do except, thereafter, go to a court to seek an order to reverse the situation. The parents had a period of one month to notify the local authority in writing of their opposition. If the parents consented to the transfer of parental rights to the council, or did not challenge it on time, parental rights were transferred to the council in the absence of a court order and the parent lost their right to resume the care of their child and indeed lost the right to claim custody of the child.

For nearly fifty years this was the law in Scotland. What chilling effect this had on parents is unclear. Likewise how much it encouraged over-reach by the authorities is unknown. But one thing is clear, instructions, or even suggestions by a Scottish local authority, made at any time between 1948 and 1995 came with the implicit addition of the words “or else”.

The errors embedded in the Clyde Report and the legislation that followed are of several types.

Firstly, the Clyde Committee ignored centuries of folk knowledge that step-parents and adults acting with parental authority who are not related to the child represent a great danger of abuse. This knowledge stretches back into the distant past, and even examples popular today are of considerable age. For example, Cinderella was first recorded in 1634 and Snow White was recorded by the Brothers Grimm in 1812. So, for centuries, we recognised that, absent the special bond between a parent and child, the risk of exploitation or abuse of a child by an adult becomes greater. This folk knowledge was discarded in favour of the state as the bringer of gifts and provider of security, safety, and welfare from the cradle to the grave. In other words, when the new ideology ran up against the old wisdom, the old wisdom was thrown away.

Secondly, it assumes that local authority committees are trustworthy and not susceptible to human failings, weakness, and sin. Now we sadly know that this is not true, surely we knew this also in the 1940s.

Take for example the London Burgh of Lambeth, where children were abused on an industrial scale. A brief extract from the 2021 report by Professor Alexis Jay shows a little of the magnitude of the suffering of the children in that local authority’s care:

It is hard to comprehend the cruelty and sexual abuse inflicted on children in the care of Lambeth Council over many years, by staff, by foster carers and their families, and by volunteers in residential settings. With one or two exceptions, a succession of elected members and senior professionals ought to have been held accountable for allowing this to happen, either by their active commission or complicit omission. Lambeth Council was only able to identify one senior Council employee, over the course of 40 years, who was disciplined for their part in this catalogue of sexual abuse.

By June 2020, Lambeth Council was aware of 705 former residents of three children’s homes in this investigation (Shirley Oaks, South Vale and Angell Road) who have made complaints of sexual abuse. The biggest of these homes – Shirley Oaks – was the subject of allegations against 177 members of staff or individuals connected with the home, involving at least 529 former residents. It was closed in 1983. The true scale of the sexual abuse against children in Lambeth Council’s care will never be known, but it is certain to be significantly higher than is formally recorded. [emphasis added]

And it is striking that the political inheritors of the Attlee version of the welfare state, such as former Children’s Minister Margaret Hodge, when alerted to this massive abuse, decided to attack the whistleblowers rather than defend the children. In the final analysis, their loyalty was to their ideology and power it delivered, not to the children who needed help.

Finally, and perhaps most telling of all, is the mindset that the family is some mechanical contrivance, a vehicle if you will, that can be assembled from component parts to generate a nurturing childhood. A house, sufficient income, a woman, a man and just add children. With six-monthly inspections by a local authority official (an equivalent of the MoT test if you like), you have all that is needed for family life. All that is except love. For in the report and statutes of the government, love is absent - it is never mentioned. And yet this intangible is the greatest gift a child can have. With it, all manner of adversity can be overcome. Without it, the most superficially perfect childhood can become a life-long injury.

Ignoring love, and instead building state power and using it to fabricate families, was the 50-year inheritance from the Clyde committee. To call it stupid or naive is perhaps generous. Authoritarian, arrogant, and bullying are words that also come to mind. The callous disregard for the real nature of children, of childhood, and of what it is to be human is starkly obvious.

To quote again from the father of English family law Stephen Cretney:

‘almost every piece of “family” legislation … in the past century has actually worked out in a way radically different from the policy presented to the legislature as justifying the legislation in question, and has often had results quite different from those which the initiators intended’

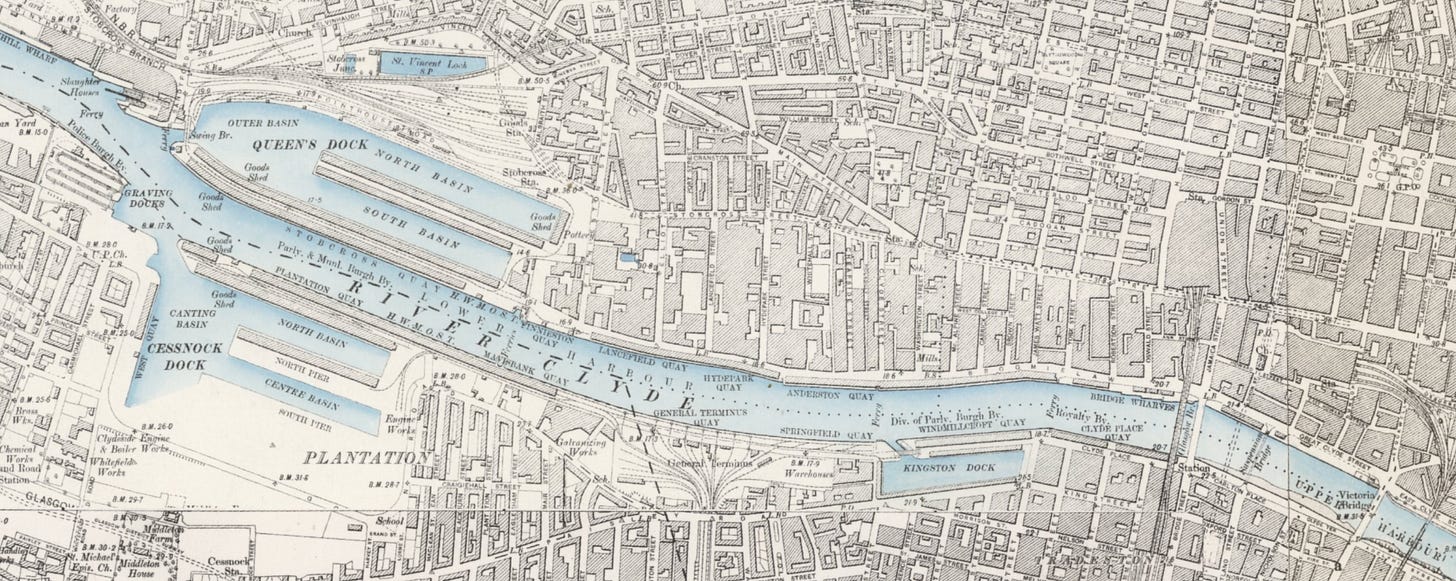

And it is this combination of a mechanical view of the family, coupled with a failure to appreciate the unintended consequences of meddling with the foundation of our society, that qualifies the Clyde Committee to be viewed as simply one more cargo heading for Glasgow’s Kingston Dock.

Thank you for writing this. The state has never shown itself to be a good carer of children. History must be remembered so it cannot be repeated.

A chilling inditement on the arrogance of the state and its onslaught against the autonomy of the family